A Study of TPL in a Multi-Species Population

The original objective of this project was to investigate a possible connection between Taylor’s Power Law (TPL) and Fisher’s

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

from matplotlib.offsetbox import AnchoredText

from scipy import odr

from scipy.interpolate import griddata

from scipy.optimize import newton

from scipy.stats import multivariate_normal

# Plotting config

%matplotlib inline

Domain

Let

Let

If we take

The

Given some

For example, if we are working in a domain with

Because of the combinatorics involved,

def build_phi(dfZ, Q_sup, stat='max', V_scale=10):

assert stat in ('min', 'max', 'mean', 'count')

# Determine ranges and shape of output

N_rng = np.arange(dfZ['N'].min(), dfZ['N'].max() + 1)

assert N_rng[0] > 0

M_rng = N_rng / Q_sup

V_min = dfZ['V'][dfZ['V'] > 0].min() # remove zero variance

V_rng = np.linspace(V_min, dfZ['V'].max(), len(N_rng) * V_scale)

shape = (len(M_rng), len(V_rng))

# This matrix counts number of data point in each 2d bin

bin_counts, _, _ = np.histogram2d(

dfZ['M'], dfZ['V'],

bins=shape,

range=[

[M_rng[0], M_rng[-1]],

[V_rng[0], V_rng[-1]]],

density=False,

)

# This matrix sums up the given statistic for each 2d bin

Phi, _, _ = np.histogram2d(

dfZ['M'], dfZ['V'],

weights=dfZ[stat],

bins=shape,

range=[

[M_rng[0], M_rng[-1]],

[V_rng[0], V_rng[-1]]],

density=False,

)

# Divide the stat sums by their corresponding counts

Phi[bin_counts>0] /= bin_counts[bin_counts>0]

# Round up or down for "max" and "min" stats

if stat == 'max':

Phi = np.ceil(Phi).astype(int)

elif stat == 'min':

Phi = np.floor(Phi).astype(int)

return Phi, N_rng, M_rng, V_rng

# Phi for Q=50 and 1<=N<=100

dfZ_a = pd.read_hdf('zeros_q50_n100.h5', 'df')

Phi_a, N_rng_a, M_rng_a, V_rng_a = build_phi(dfZ_a, 50, 'mean')

# Phi for Q=100 and 1<=N<=100

dfZ_b = pd.read_hdf('zeros_q100_n100.h5', 'df')

Phi_b, N_rngb, M_rng_b, V_rng_b = build_phi(dfZ_b, 100, 'mean')

# Plot

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 2, sharey=False)

fig.set_figwidth(12)

ax[0].pcolor(M_rng_a, V_rng_a, Phi_a.T, cmap='magma')

ax[0].set_title('$\Phi$ for $Q=50$')

ax[0].set_xlabel('Mean')

ax[0].set_ylabel('Variance')

ax[1].pcolor(M_rng_b, V_rng_b, Phi_b.T, cmap='magma')

ax[1].set_title('$\Phi$ for $Q=100$')

ax[1].set_xlabel('Mean')

ax[1].set_ylabel('Variance');

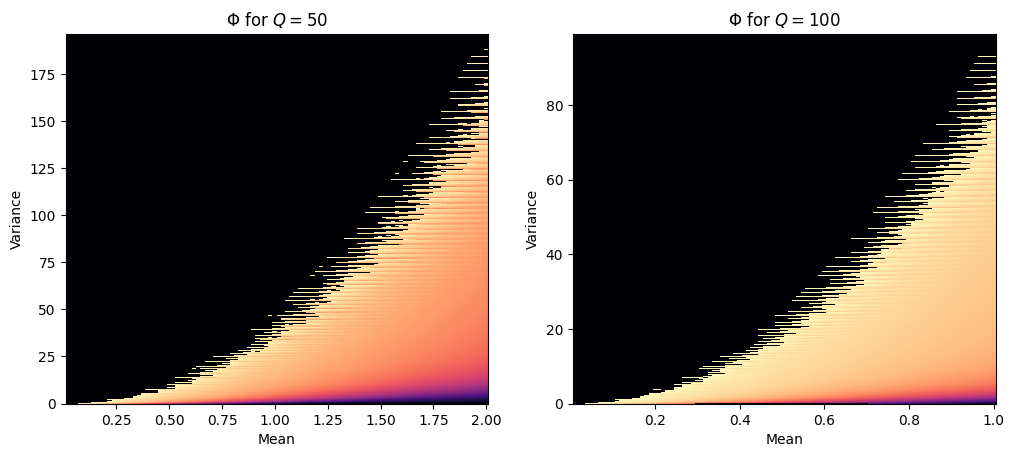

The two heatmaps above show

Random populations

def orth_fit(x, y):

odr_obj = odr.ODR(odr.Data(x, y), odr.unilinear)

output = odr_obj.run()

return output.beta

def calc_rho(pdf, Phi, Q, Q_sup):

pdf = pdf.T.copy()

pdf[Phi<=0] = 0 # get rid of impossible values

pdf /= pdf.sum()

# For each (M,V), if Phi(M,V) zeros are expected (of Q_sup bins),

# then to the probability of getting Q zeros in a row at the beginning

# is this product.

lam = 1

for i in range(Q):

rem = Phi-i

rem[rem<0] = 0

lam *= rem / (Q_sup-i)

rho = (pdf * lam).sum()

return rho

class Population:

def __init__(self, path, Q_sup=None, N_sup=None, S_sup=None, name=None):

self.Q_sup = 50 if Q_sup is None else Q_sup

self.N_sup = 100 if N_sup is None else N_sup

self.S_sup = 200 if S_sup is None else S_sup

self.name = 'Population' if name is None else name

self.Q_cols = np.array([f'Q{i}' for i in range(self.Q_sup)]) # column names

self.df_path = path

self.df = pd.read_hdf(self.df_path, 'df')

self.dfZ_path = f'zeros_q{self.Q_sup}_n{self.N_sup}.h5'

self.dfZ = pd.read_hdf(self.dfZ_path, 'df')

self.Phi, self.N_rng, self.M_rng, self.V_rng = build_phi(self.dfZ, self.Q_sup, 'max')

self.pdf_true = self.get_pdf(self.df['M'].to_numpy(), self.df['V'].to_numpy())

self.dfS = self.simulate()

def get_pdf(self, M, V, allow_singular=False):

# Fit a 2D normal distribution to the data (in log space)

M_ln = np.log(M)

V_ln = np.log(V)

rv = multivariate_normal(

mean=[np.mean(M_ln), np.mean(V_ln)],

cov=np.cov(M_ln, V_ln),

allow_singular=allow_singular,

)

Xm, Ym = np.meshgrid(self.M_rng, self.V_rng)

pos = np.dstack((Xm, Ym))

pdf = rv.pdf(np.log(pos))

pdf /= pdf.sum()

pdf[np.isclose(pdf, 0)] = 0

pdf /= pdf.sum()

return pdf

def simulate(self, shuffle=False):

# Select bin data

Q_cols = self.Q_cols.copy()

if shuffle:

np.random.shuffle(Q_cols)

df = self.df[Q_cols].copy()

# Count unique species across entire domain, starting from left bin

dfS = pd.DataFrame({

'Q': range(1, len(Q_cols)+1),

'S': np.count_nonzero(

np.cumsum(df, axis=1),

axis=0),

})

for i in range(len(Q_cols)):

cols = Q_cols[:i+1]

_df = df[cols].copy()

_N = np.sum(_df, axis=1)

_M = np.mean(_df, axis=1)

_V = np.var(_df, axis=1)

_df['N'] = _N

_df['M'] = _M

_df['V'] = _V

# Discard species with zero mean or variance

_df = _df[(_df['M'] > 0) & (_df['V'] > 0)]

tpl_b, tpl_a, rho = np.nan, np.nan, np.nan

if len(_df.index) > 1:

M_ln = np.log(_df['M'].to_numpy())

V_ln = np.log(_df['V'].to_numpy())

tpl_b, tpl_a_ln = orth_fit(M_ln, V_ln)

tpl_a = np.exp(tpl_a_ln)

# Note: using true PDF

pdf = self.pdf_true

rho = calc_rho(pdf, self.Phi, i+1, self.Q_sup)

dfS.loc[i, ['b', 'a', 'rho']] = tpl_b, tpl_a, rho

return dfS

# Population datasets

populations = [

Population('pop_4_q50_n100_s200.h5', Q_sup=50, name='A1'),

Population('pop_5_q50_n100_s200.h5', Q_sup=50, name='A2'),

Population('pop_6_q50_n100_s200.h5', Q_sup=50, name='A3'),

Population('pop_1_q100_n100_s200.h5', Q_sup=100, name='B1'),

Population('pop_2_q100_n100_s200.h5', Q_sup=100, name='B2'),

Population('pop_3_q100_n100_s200.h5', Q_sup=100, name='B3'),

]

def scatter_plot(pop, ax=None):

if ax is None:

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 1)

M = pop.df['M']

V = pop.df['V']

M_ln = np.log(M)

V_ln = np.log(V)

N_rng = pop.N_rng

M_rng = pop.M_rng

ax.scatter(M, V, 1, marker='+')

ax.set_xscale('log')

ax.set_yscale('log')

ax.set_title(f'Population {pop.name}')

# ax.set_xlabel('M')

# ax.set_ylabel('V')

V_bounds = np.zeros((len(M_rng), 2))

for i, n in enumerate(N_rng):

s = np.zeros(pop.Q_sup)

s[0] = n

max_ = s.var()

quo, mod = np.divmod(n, pop.Q_sup)

s[:mod] = quo + 1

s[mod:] = quo

assert s.sum() == n

min_ = s.var()

V_bounds[i] = (min_, max_)

ax.plot(M_rng, V_bounds[:, 0], '--', color='tab:gray')

ax.plot(M_rng, V_bounds[:, 1], '--', color='tab:gray')

est_b, est_a_ln = orth_fit(M_ln, V_ln)

est_a = np.exp(est_a_ln)

V_tpl = np.exp(np.log(est_a)+est_b*np.log(M))

ax.plot(M, V_tpl, 'b-', linewidth=1)

# ax = plt.gca()

tpl_text = '$b = %.2f$ $a = %.2f$' % (est_b, est_a)

at = AnchoredText(

tpl_text, loc='upper left', prop=dict(size=8), frameon=True)

at.patch.set_boxstyle('round, pad=0., rounding_size=0.2')

ax.add_artist(at)

# Plot

fig, ax = plt.subplots(2, 3, sharey=True)

fig.set_figheight(8)

fig.set_figwidth(16)

plt.subplots_adjust(hspace=0.4)

for i, pop in enumerate(populations):

row = int(i/ax.shape[1])

col = i % ax.shape[1]

scatter_plot(pop, ax[row][col])

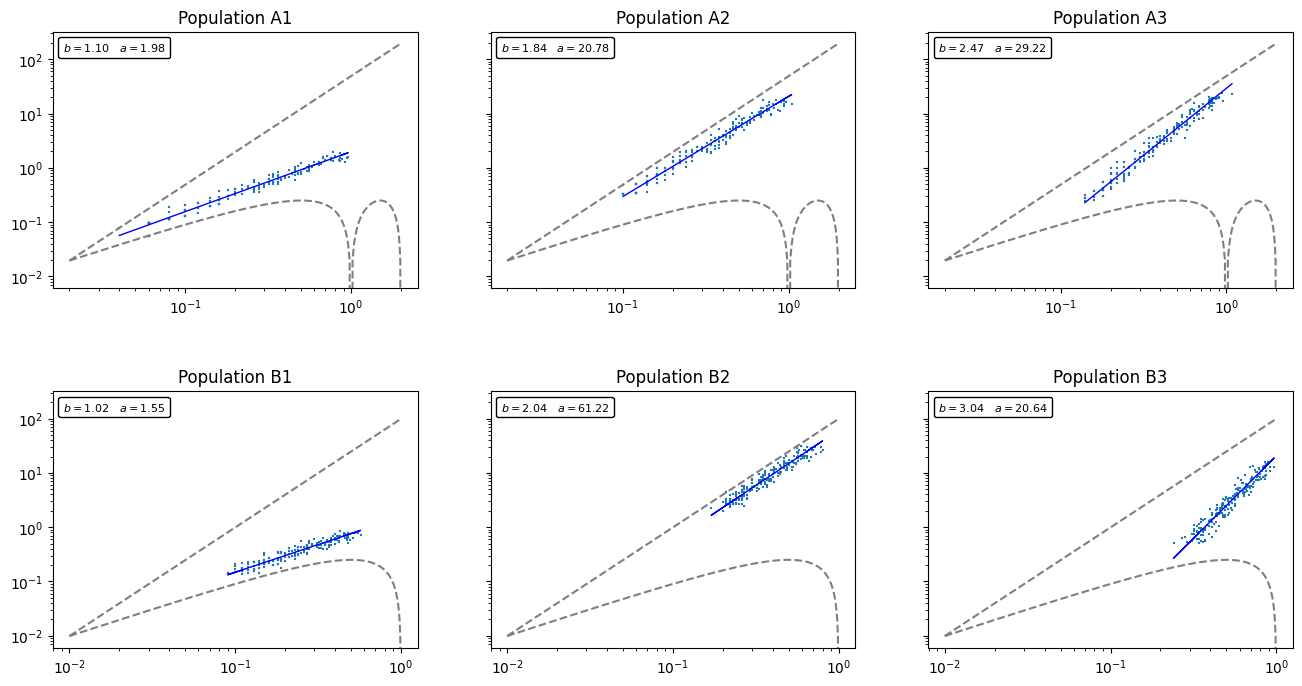

I’ve generated 6 random multi-species populations. The first 3 (labels starting with A) assume B) assume

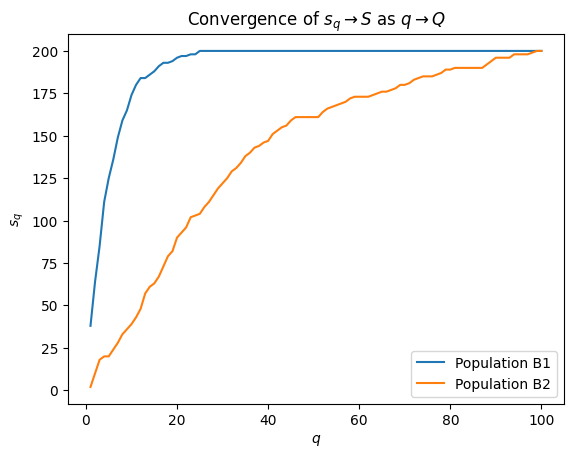

The question I’m interested in: How do the distributions of these different populations affect the expected species count

It turns out that when a population consists mainly of highly aggregated species, then it will take longer for

As an illustration, let’s plot out

for i in [3, 4]:

pop = populations[i]

plt.plot(pop.dfS['Q'], pop.dfS['S'], label=f'Population {pop.name}')

plt.legend()

plt.xlabel('$q$')

plt.ylabel('$s_q$')

plt.title('Convergence of $s_q \\rightarrow S$ as $q \\rightarrow Q$');

Notice the clear difference in shape between the convergence lines of populations B1 and B2. Population B1 has less variance than B2 (therefore more uniform), so we can expect the various species to be discovered at earlier iterations

So, in theory, if you know how much as been sampled and you have a good idea as to the degree of aggregation in the population, then you should be able to place an estimate on the absolute total number of species.

Estimating

Let

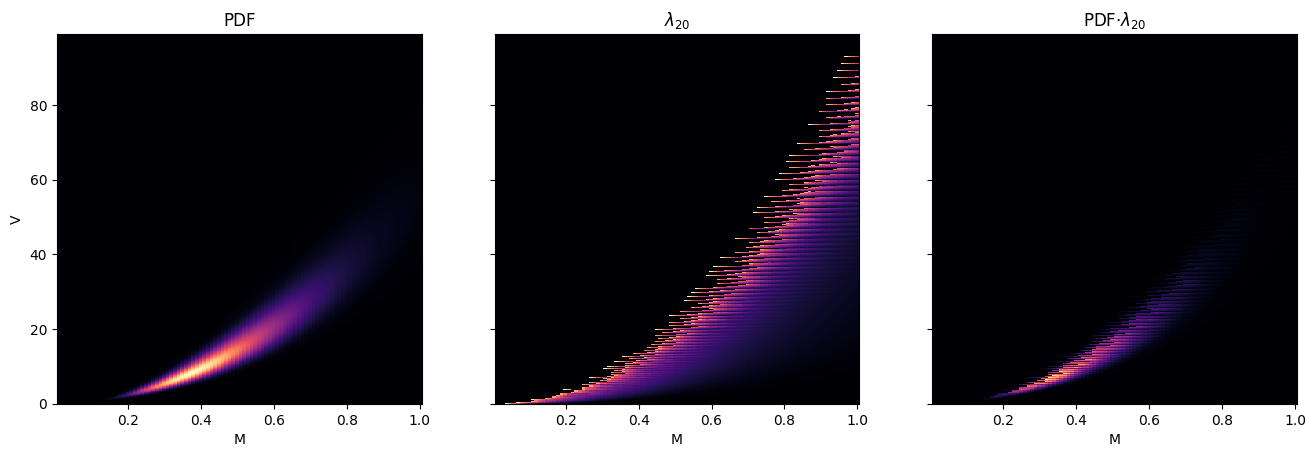

Recall from before that the probability that a species with a given

If

We are essentially piece-wise multipying

Rewritten we have a formula for estimating

The key concept is the estimation of

lam = 1

q = 20

for i in range(q):

rem = Phi_b-i

rem[rem<0] = 0

lam *= rem / (pop.Q_sup-i)

pop = populations[4] # B2

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 3, sharey=True)

fig.set_figwidth(16)

ax[0].pcolor(M_rng_b, V_rng_b, pop.pdf_true, cmap='magma')

ax[0].set_title('PDF')

ax[0].set_ylabel('V')

ax[0].set_xlabel('M')

ax[1].pcolor(M_rng_b, V_rng_b, lam.T, cmap='magma')

ax[1].set_title('$\lambda_{%i}$' % q)

ax[1].set_xlabel('M')

ax[2].pcolor(M_rng_b, V_rng_b, pop.pdf_true * lam.T, cmap='magma')

ax[2].set_title('PDF$\cdot\lambda_{%i}$' % q)

ax[2].set_xlabel('M');

The first plot is the PDF of Population B2 in

Results

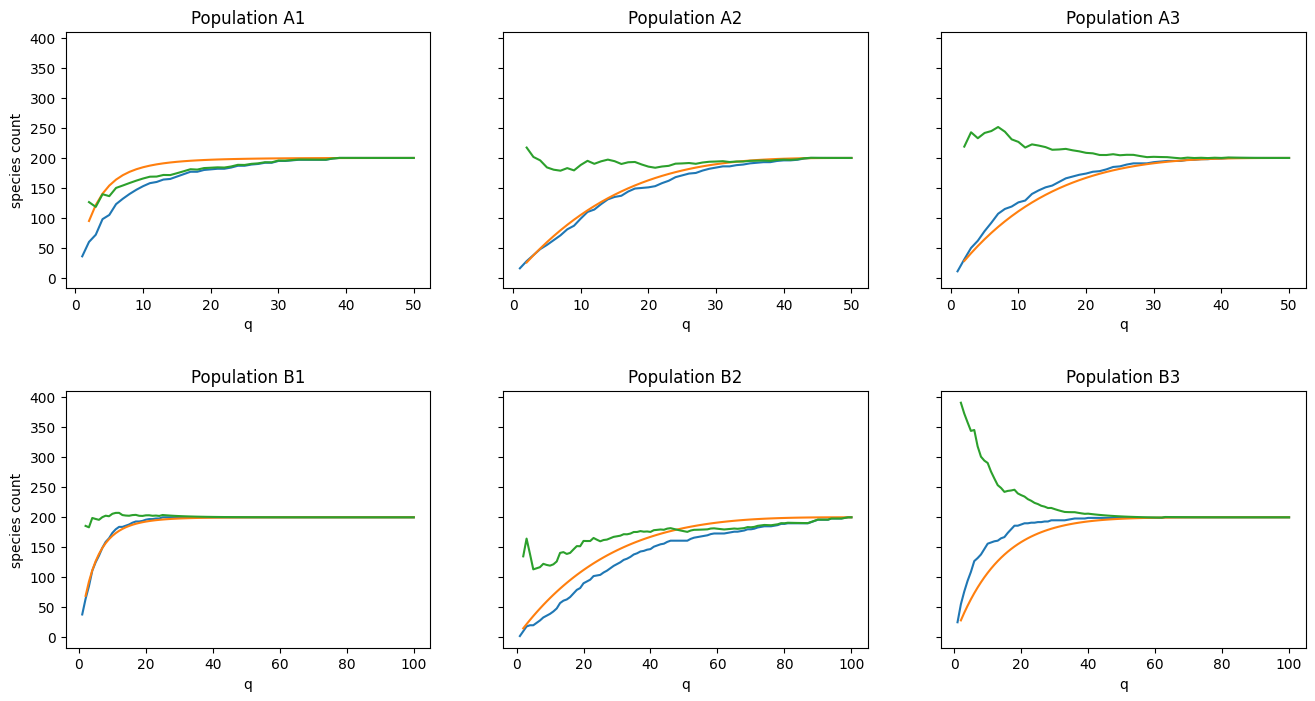

Now let’s test the theory for each of the 6 populations.

def sim_plot(pop, ax=None, shuffle=False):

if ax is None:

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 1)

dfS = pop.simulate(shuffle=True) if shuffle else pop.dfS

ax.plot(dfS['Q'], dfS['S'])

ax.plot(dfS['Q'], pop.S_sup * (1-dfS['rho']))

ax.plot(dfS['Q'], dfS['S'] / (1-dfS['rho']))

ax.set_title(f'Population {pop.name}')

ax.set_xlabel('q')

# Cumulative species count

fig, ax = plt.subplots(2, 3, sharey=True)

fig.set_figheight(8)

fig.set_figwidth(16)

plt.subplots_adjust(hspace=0.4)

for i, pop in enumerate(populations):

row = int(i/ax.shape[1])

col = i % ax.shape[1]

sim_plot(pop, ax=ax[row][col], shuffle=False)

ax[0][0].set_ylabel('species count')

ax[1][0].set_ylabel('species count');

How to interpret these plots:

- The blue line is the observed number of species

as . - The green line is our estimate of

given (we expect this line to approach in all cases). - The orange curve is what we expect our species curve to look like given

and prior knowledge of . The closer the blue and orange lines are together, the better our estimate of will be (green line).

Visual inspection yields mixed results:

- Populations A2, A3, and B1 show excellent alignment

- Populations A1 and B2 show “okay” alignment

- Population B3 shows very poor alignment

Discussion

First of all, the procedure for estimating

Secondly, it can be seen clearly from the results that the procedure is not fool-proof. In particular, predictions for Populations A1 and B2 were farther off than I’d like, while B3 was way off. My hunch is that these outliers are due to a failure to take into account the higher-order moments of

It may be possible to side-step both issues by applying a non-linear machine learning algorithm (e.g. neural network) to the available data. There is clearly a strong connection between the population distribution,

Now let’s consider the

Possible lead?

Is it possible to somehow remove the need for prior knowledge of

Given:

- Let

be the PDF of all species in space after all samples have been taken. - Let

be the PDF of observed species after samples taken. - Let

be the PDF of unobserved species after samples taken.

It follows that

We can write

If

Thus we have a relation between

Here we have a relation between two unknowns. There’s not much more to be done without additional traction. Perhaps this can be formulated as an optimization problem in which we simultaneously solve for

Here’s a thought experiment. Let’s say you’ve taken

So, given our first sample, right off the bat there are certain

References

- Taylor, R. A. (2019). Taylor’s power law: order and pattern in nature. Academic Press.

- Fisher, R. A., Corbet, A. S., & Williams, C. B. (1943). The relation between the number of species and the number of individuals in a random sample of an animal population. The Journal of Animal Ecology, 42-58.